What 2025 Taught Us About EdTech Leadership and What 2026 Demands Next

Insights from CoSN's 2025 State of EdTech District Leadership report

With winter weather settling in where I live, I’ve taken a little time to cozy up with my e-reader and work through some of my stack of “I’ll read this later” reports, articles, and notes that piled up over the fall semester. One of those was CoSN’s 2025 State of EdTech District Leadership report, released back in May and promptly buried under day-to-day urgencies.

The 2025 CoSN State of EdTech District Leadership report didn’t introduce shocking revelations or sudden pivots. Instead, it quietly confirmed something many district leaders already felt in their bones: the role of EdTech leadership has expanded faster than the systems designed to support it.

That makes 2025 less of a closing chapter and more of a diagnostic report. If we read it carefully, it tells us where K12 technology leadership is strong, where it is stretched thin, and where 2026 will expose cracks if we keep operating the same way.

2025 Was the Year the Job Finally Caught Up With the Title

For years, “EdTech leader” sounded instructional. Devices, learning platforms, maybe some professional development. The 2025 data makes it unambiguous: that framing is obsolete.

EdTech leaders are now accountable for instructional technology, administrative systems, cybersecurity, physical security, identity management, data privacy, and increasingly, AI governance. Many are responsible for doors (59%), cameras (50%), HVAC systems (37%), and emergency communications alongside classroom tools.

This could once be chalked up to mission creep, but it’s safe to say that today this creep has turned into the new mission reality.

What stands out in the 2025 report is not resistance to this expansion. Maybe it’s education’s long-standing acceptance of the “other duties as assigned” pitfall, but most leaders already accept it. What is missing is a corresponding redesign of authority, staffing models, funding structures, and risk ownership. If everything becomes “technology,” then leadership design matters more than tools.

AI in 2025: From Curiosity to Dependency

By 2025, generative AI had moved decisively out of the novelty phase. Most districts (80%) were experimenting, piloting, or actively using AI tools. Very few, only 1%, were banning them outright. That shift alone is telling.

The deeper signal, however, is not adoption, but how governance lagged behind usage.

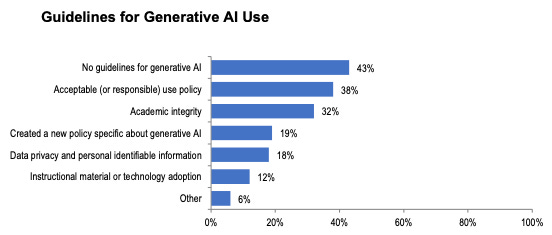

Many districts allowed AI based on use case, but nearly half (43%) lacked formal guidelines. Policies were often retrofitted into acceptable use or academic integrity documents, rather than treated as a new class of system risk.

That approach was survivable in 2024 and 2025, but it will be much harder to defend in 2026 as AI is no longer just a classroom issue. It now intersects with:

Identity and access management

Data classification and retention

Vendor risk and procurement

Incident response and misinformation

Assessment design and instructional integrity

In other words, AI is becoming infrastructure. And infrastructure without governance becomes liability.

The 2025 report shows districts knew this was coming. The open question for 2026 is whether governance maturity will catch up to technical reality.

Cybersecurity: Investment Without Confidence

One of the most striking tensions in the report sits in the cybersecurity data.

Districts are spending more. Monitoring, detection, and response dominate cybersecurity budgets. Outsourcing is common, often out of necessity rather than preference. Cyber insurance is changing, becoming more expensive and more restrictive.

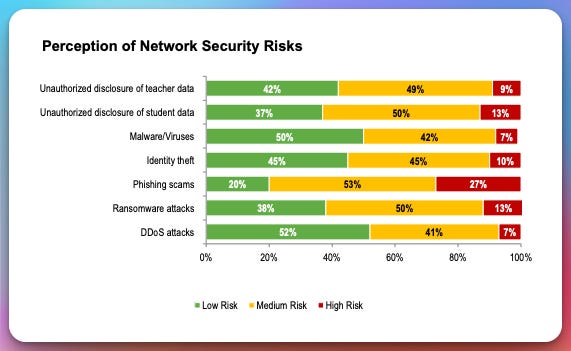

Yet at the same time, most EdTech leaders rated their districts’ risk exposure as low to moderate across most threat categories. Only 27% of respondents rated phishing as a high risk, and only 13% rated ransomware or student data disclosure as a high risk.

That mismatch should make us uncomfortable.

If districts were underinvesting and underestimating risk, the story would be simple. But 2025 shows investment paired with optimism, even as ransomware, identity compromise, and data exfiltration continue to plague better-funded sectors.

This suggests a perception gap, not ignorance. Tools are being purchased, controls are being implemented, but threat modeling may still be abstract. Student data, staff identities, and operational continuity are treated as protected because controls exist, not because adversaries have been realistically considered.

It can feel like educational leadership is at the front-end of the Dunning-Kruger curve: money is being invested more in cybersecurity so confidence is high. Unfortunately, threat modeling is relatively immature in K12 so many EdTech leaders don’t know what they don’t know about the current threat landscape.

As we move into 2026, this gap matters more than budget size. Reduced federal training support and shifting insurance requirements will expose districts that confuse compliance motion with resilience.

for educational technology leaders interested in learning more about the specific threats facing K12, the K12 Security Information eXchange (K12 SIX / k12six.org) is a great starting point to learn about existing and emerging cyberthreats facing K12.

Funding Reality: Emergency Thinking Is Over

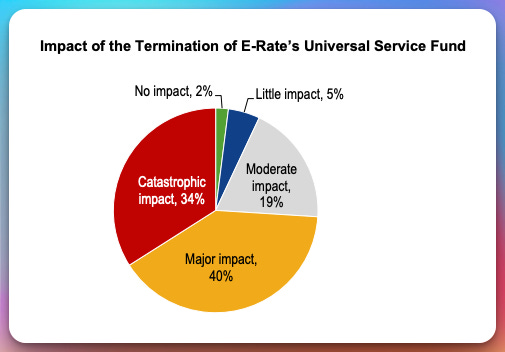

If one finding in the 2025 report deserves board-level attention, it is the near-universal alarm around E-Rate.

The data is blunt. Loss or disruption of E-Rate funding would be catastrophic or severely damaging for most districts, across all geographies. Overall, 74% of respondents said the loss of E-Rate would have a significant negative impact, with 40% describing the disruption as major and 34% as catastrophic. Connectivity is no longer a support service; it is the backbone of instruction, assessment, safety systems, and AI-enabled learning.

The lesson for 2026 is not simply “protect E-Rate.” It is broader.

The emergency funding era trained districts to accelerate. Devices were purchased. Platforms were deployed. Gaps were closed quickly. What it did not train districts to do was sustain.

As federal relief fades, technology strategy must shift from acceleration to endurance. That means:

Justifying infrastructure as operational necessity

Planning refresh cycles realistically

Treating cybersecurity and connectivity as ongoing obligations, not projects

Making political and community cases for technology that are grounded in continuity, not innovation

2026 will reward districts that planned for sustainability earlier and punish those still operating on temporary assumptions.

The Human Cost of Role Expansion

Perhaps the most under-discussed signal in the report is the quiet normalization of overload.

EdTech leaders are increasingly cabinet-level participants. That is progress. But they are also absorbing more responsibilities without proportional staffing growth or clearer decision authority.

The data shows responsibility expanding faster than organizational design.

When access control, security cameras, and building systems land under the technology umbrella, the question is no longer “can IT handle this?” but rather “who owns the risk when it fails?”

In 2026, districts that do not clarify ownership, authority, and escalation paths will feel this strain most acutely. Burnout is not just a staffing issue. It is a governance issue.

What 2026 Actually Requires

The 2025 CoSN report does not demand new tools. It demands new thinking.

As districts move into 2026, three mindset shifts stand out:

From experimentation to governance

AI, cybersecurity, and data systems must move from pilot mode to policy-backed operations.From perceived safety to evidence-based risk

Confidence should be grounded in threat modeling, not tool inventories.From role expansion to role redesign

If EdTech leaders are responsible for everything digital, districts must redesign authority, staffing, and expectations accordingly.

2025 told us where we stand. 2026 will test whether we listened.